Heat stress in swine: facts, problems and support options

Our climate is changing. Periods of heat stress for farm animals will increase in frequency and/or in length. This will - amongst other things - affect the welfare and production capacity in swine production. Let’s review some facts about heat stress in swine, some of the problems that occur and some of the support options that can help the animals to cope with periods of heat.

Facts

Pigs are endotherms, they generate their own internal body heat and possess self-regulating processes to maintain their core body temperature within a certain interval optimal for survival. For pigs, this interval is 38.7- 40.0 °C. Heat stress occurs when the pig is unable to maintain its body core temperature within this optimal interval 38.7- 40.0 °C.

Fact: the upper temperature of the thermo neutral zone varies

If the temperature increases above the pig’s thermo neutral zone they will need help to maintain their body core temperature. What this thermo neutral zone is, depends on age, size and reproductive status but also humidity, ventilation and other environmental factors. Table 1 shows the approximate temperature where a decrease in performance due to high temperatures can be observed.

Table 1. The temperatures were heat stress starts to impact animal productivity. In large animals the negative effects can already be seen at a quite modest temperature increase.

|

Animal category |

Ambient temperature |

|

Pig 25 kg |

27 °C |

|

Pig 50 kg |

25 °C |

|

Pig 75 kg |

23 °C |

|

Nursery sow |

22 °C |

Fact: pigs can dissipate body heat via radiation, conduction, convection and evaporation

A feral pig would seek out shade and a nice mud pool were the body heat can be conducted to the cool water. This strategy to seek out a new environment is usually not an option for production animals. Instead they try to find a spot where they can lie flat on the floor and convey heat to the concrete if possible. The most effective way to help pigs to lose heat is to adapt their environment by providing shade, air conditioned houses, install fans, sprinklers etc. but this is very costly.

Fact: Pigs are more sensitive to heat stress that other farm animals

This is due to the fact that pigs barely have any sweat glands, they have relatively small lungs compared to their body size and they have a thick subcutaneous layer of adipose tissue.

Fact: Today’s highly productive pigs generate more endogenous heat resulting in reduced tolerance to heat stress

Modern breeds are genetically selected for their productive traits such as lean tissue accretion, high milk yield and high prolificacy and as such produce more endogenous heat making them more vulnerable to heat stress.

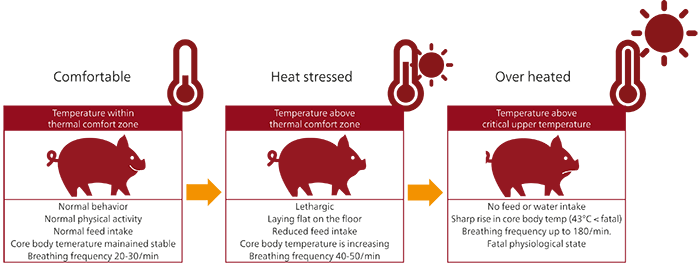

Figure 1. Overview of changes in animal behavior when temperature changes from comfortable to life critical.

Problems

The production consequences will vary from more days to market due to reduced growth rate to actual loss of animals. Other costs related to heat stress may be harder to measure.

Problem: heat stress can also result in reduced carcass classification

Heat stress affects metabolic pathways. Lean tissue accretion is limited due to reduced protein synthesis in combination with increased muscle proteolysis to provide energy. The ability to use adipose tissue as an energy source is reduced combined with increased lipogenesis resulting in increased adipose tissue accretion. This results in an unfavorable carcass composition.

Problem: reduction of productivity parameters

Heat stress in sows can result in reduced feed intake, reduced fertility and reduced milk production. Reduced milk production may lead to impaired piglet growth. The reduction in milk production is actually larger than could be expected from the reduction in feed intake alone. The gap is explained by the increased blood flow to the skin leaving less blood to support the processes in the mammary glands resulting in decreased milk production.

Problem: heat stress can have a genetic impact on offspring

Heat stress, especially during first half of gestation, may have an epi-genetic impact on offspring. Piglets exposed to in utero heat stress are born with an increased body core temperature leaving them extra sensitive to heat stress during their life. It has also been shown that later in life (early finishing phase) these pigs have different body compositions, they will have less lean meat accretion and increased adipose tissue accretion.

Problem: heat stress can start a negative spiral of vital physiological functions

When heat stressed animals shunt their blood flow to the skin to increase the radiant heat dissipation, the gastrointestinal blood vessels constrict in order to maintain blood pressure. This means less blood circulating in the gastro-intestinal system to absorb nutrients from the feed and to supply the intestinal cells with nutrients and oxygen which in turn leads to decreased FCR, reduced growth or milk production and eventually also to reduced cell wall integrity and leaky gut, increasing the risk for infections. If the heat stress continues, the increased respiratory rate may lead to respiratory alkalosis, which is lethal if not reversed. The pigs also start to drink excessively leading to a loss of electrolytes via the urine which may result in diarrhea, further increasing the severity of the situation.

Support options

If rebuilding the barns is not an option, there are other things you can do to help the pigs to cope with heat stress.

Support: plenty of cool and clean drinking water

Animals drink approximately twice as much as they eat and when feeling unwell they stop eating before they stop drinking. Providing clean cool drinking water at all times really helps them. Warm temperatures increase the growth rate of unwanted bacteria and other microorganisms. Pay extra attention to the water quality. Organic acids have shown to inhibit unwanted bacteria. Electrolytes can also be supplied via the water if needed.

Support: make smart adjustments to feeding times

Avoid feeding during the hottest period of the day, as animals are more likely to consume feed when it’s cooler. Feed small frequent meals to stimulate feed intake. Increase the fat content, reduce crude protein and assess the fiber quality of the diet. Fat metabolism generates less endogenous heat than metabolizing protein and fiber fermentation in the large intestine. Avoid feeding excess protein to reduce the metabolic heat production but pay attention to the amino acid profile and content to fulfill the dietary need for the pig.

Support: clever use of feed formulation and additives

As stated above, heat stress may lead to reduced intestinal integrity which increase the risk of antigens entering the body and causing inflammatory responses and secondary infections. To support intestinal integrity and repair, feed additives such as butyric acid sources and anti-oxidants such a vitamin E and vitamin C, selenium and betaine can be supplied via the feed. The dietary electrolyte balance deserves some extra attention during periods of heat stress to correct electrolyte imbalances.